Healthy living on a healthy planet

Our lifestyle is making us ill and is destroying the natural life-support systems. In the vision of ‘healthy living on a healthy planet’, human spheres of life – what we eat, how we move, where we live – are designed to be both healthy and environmentally compatible, and planetary risks – climate change, biodiversity loss, pollution – have been overcome.

Overview

The vision of healthy living on a healthy planet focuses on the inseparability of human health and nature, and thus on an extended understanding of health. The World Health Organization’s comprehensive definition of human health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” is dependent on a ‘healthy’ Earth – with functioning, resilient and productive ecosystems and a stable climate.

More about this topic

In essence, the goal is to explore and implement development paths that do justice to people and nature. It is about healthy lifestyles that simultaneously protect nature – about what we eat, how we move and where we live. It is about framework conditions that make these lifestyles possible. It is about preserving natural life-support systems (halting climate change, biodiversity loss and global pollution), preparing our health systems for the challenges ahead and harnessing their transformative potential. It is about education and science that can make the vision of healthy living on a healthy planet a reality. And finally, it is about reaching an agreement on this guiding principle at the international level, because without international cooperation, this vision cannot be achieved.

Shaping areas of life: what we eat, how we move, where we live

How we eat, move, live, work and spend our leisure time – all these aspects of life affect our health and, at the same time, have consequences for the climate, ecosystems and the spread of harmful substances. If healthy, environmentally friendly behaviour is to become attractive or even possible in the first place, the corresponding external conditions must also be conducive. Using selected examples from key areas of life, the WBGU shows which conditions and behaviours could be desirable and achievable.

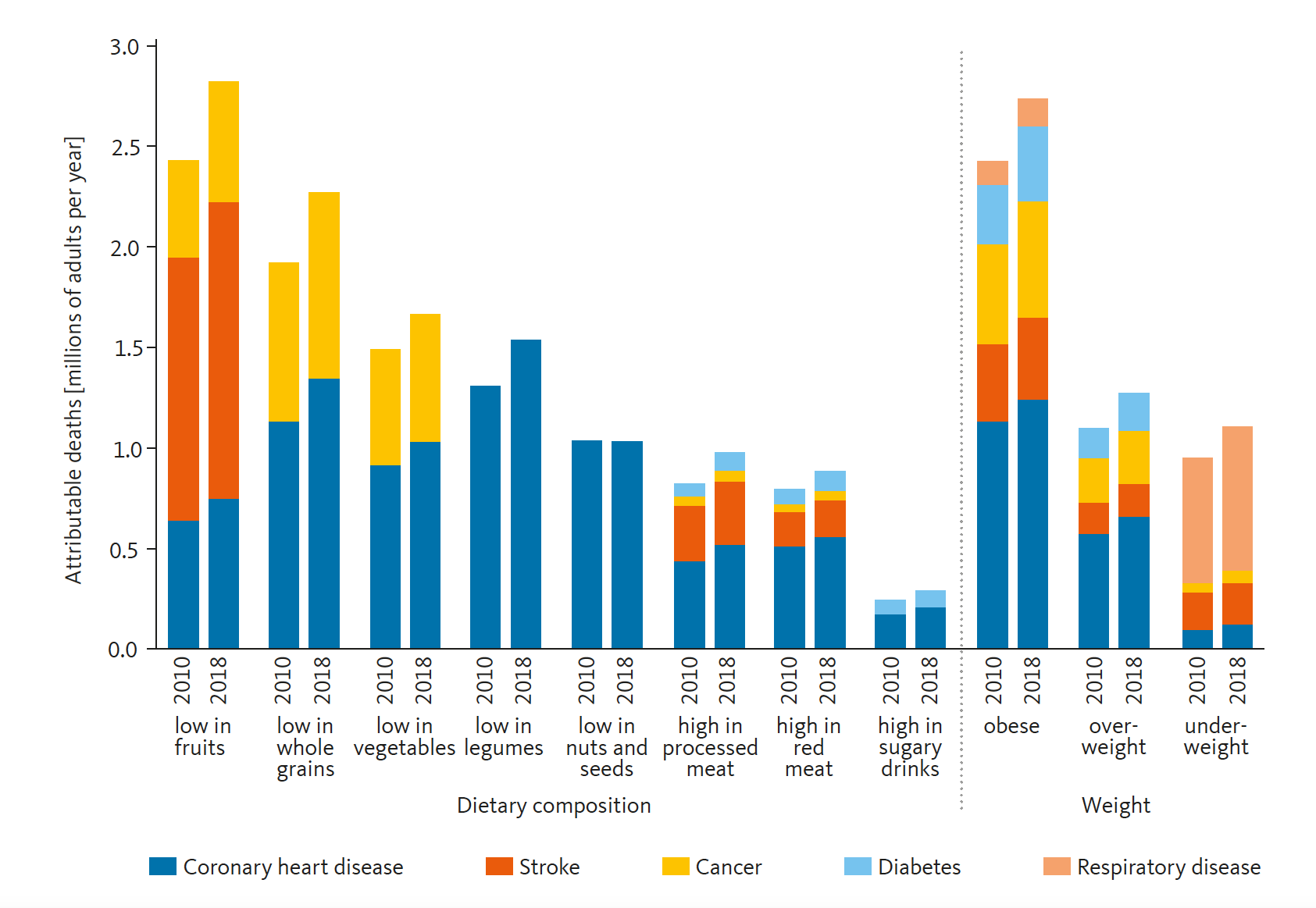

Ways to a healthy diet – for everyone: Whether the internationally agreed climate and biodiversity targets can be achieved will also depend on the transformation from environmentally damaging and unhealthy diets to a sustainable, plant-based, nutrient-rich and diverse diet. This transformation leads away from excessive consumption of animal products and ultraprocessed foods and frees up land reserves previously tied up in animal feed production. The reassignment of land use should benefit human food production, climate change mitigation and – by restoring ecosystems – biodiversity conservation. Such a transformation not only has ecological and economic benefits, it also significantly promotes human health (Figure 1).

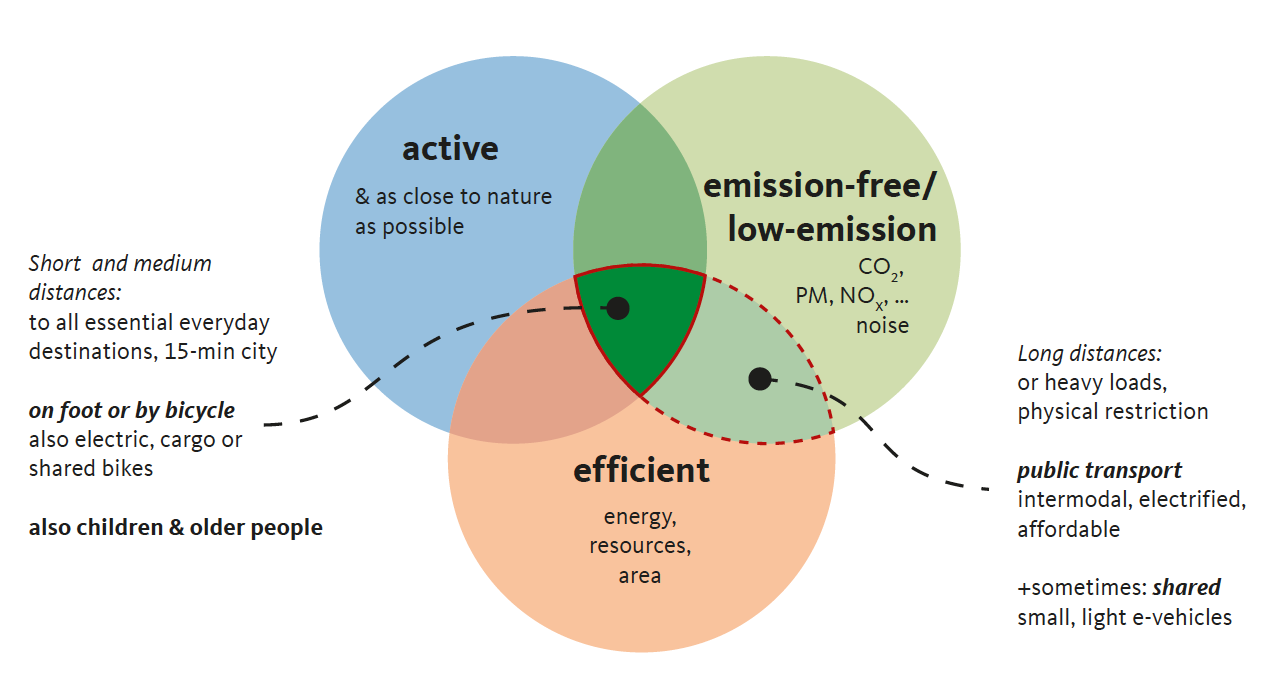

Activity-friendly environment – environment-friendly activity: Changing people’s patterns of physical activity offers enormous potential for health and the environment (Figure 2). Currently, however, physical activity is sidelined in all areas of life – everywhere from employment, housework and education to mobility and leisure time. Very many people fail to reach the WHO’s recommendations for physical activity and spend many hours sitting. Physical inactivity and sedentary behaviour (i.e. sitting or lying when awake) are major risk factors for many non-communicable diseases, and the means used to avoid physical activity often harm the environment and people. Car traffic in particular consumes a lot of energy, resources and space, and causes air pollution, climate damage and noise. It restricts the freedom of movement, safety, social interactions and participation of people in their living environment and of all those who walk, cycle or rely on public transport, e.g. children and many older and poorer people. Increasing environment-friendly physical activity and mobility requires an activity-friendly environment.

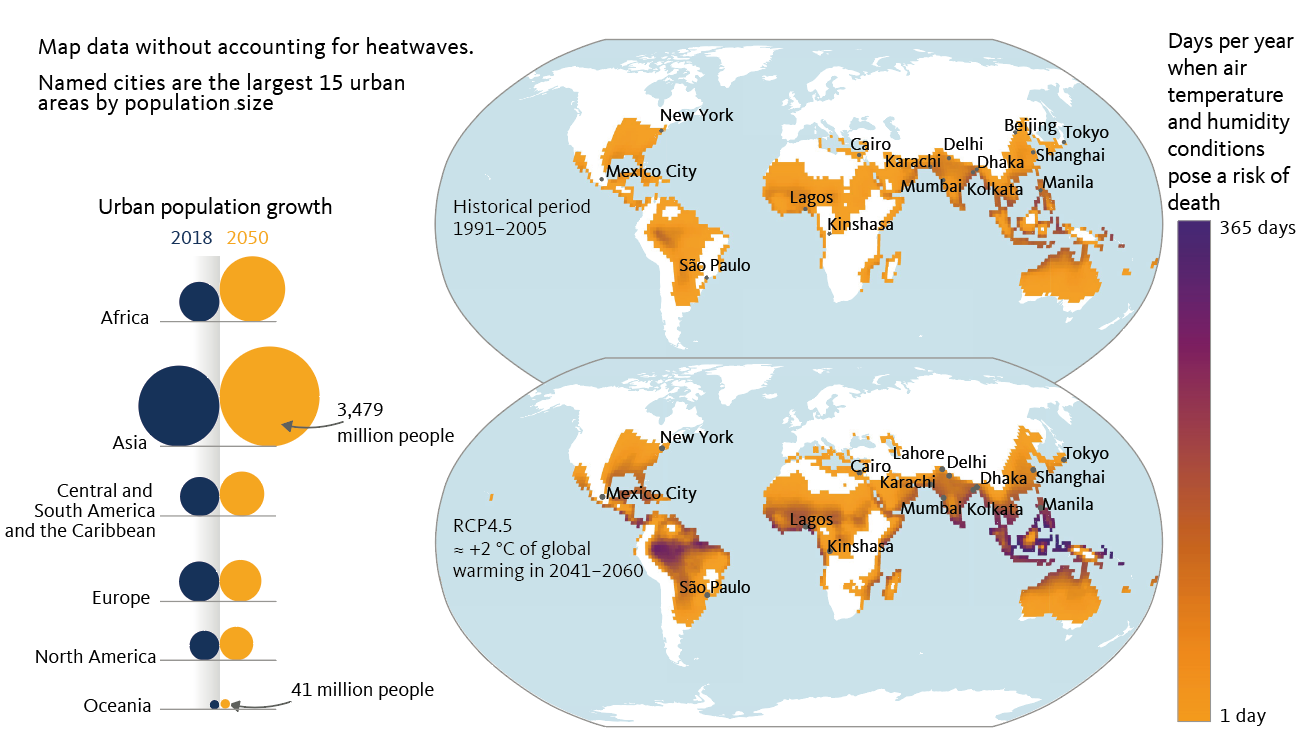

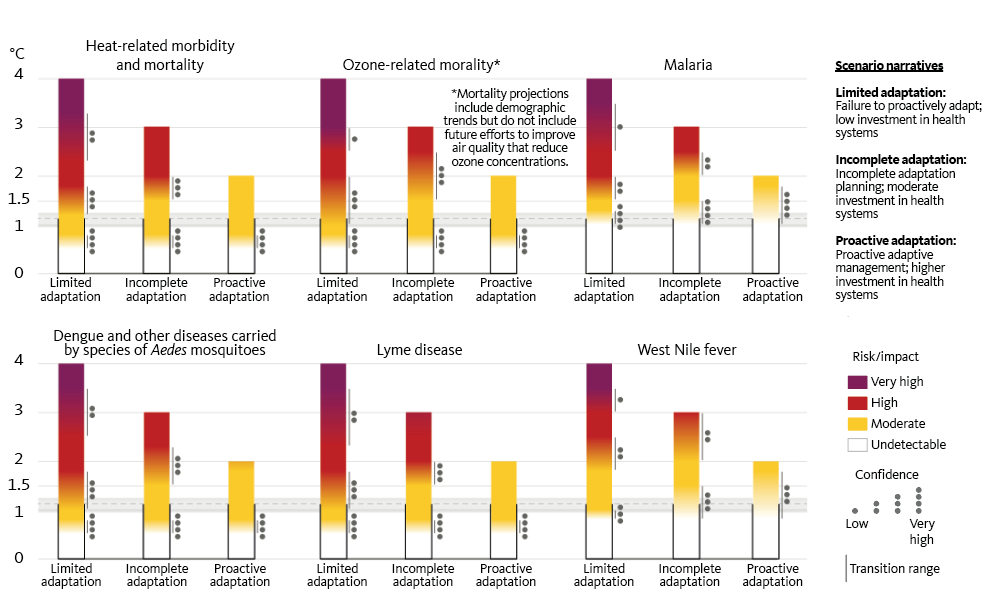

Housing in health-promoting and sustainable settlements: The way residential areas are built also determines how healthily people can live there. Cities and residential areas cause climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution; at the same time they are impacted by them (Figure 3). This offers starting points for synergies which can be used to accelerate the transformation towards sustainability. This not only applies to the global need to improve both the residential environment and the building and housing stock. The need to build new urban settlements for around 2.5 billion people by the middle of the century offers a window of opportunity for advancing sustainable and healthy construction with climate-friendly building materials on a large scale in a short period of time – and for avoiding unsustainable path dependencies. This concerns, among other things, building materials, recycling, the design of cities and urban infrastructures, and health-promoting living conditions.

Managing planetary risks: climate change, biodiversity loss, pollution

In addition to climate change and biodiversity loss, globally rising pollution is a major health risk for people and nature.

Promoting climate-change mitigation and biodiversity conservation: Climate change is developing into the biggest threat to human health and is inextricably linked to the progressive loss of biodiversity. Particularly promising for addressing these crises and the associated risks for nature and people is a nexus approach which integrates climate-change mitigation and biodiversity conservation, harnesses synergies and constructively address-es trade-offs. The WBGU recommends supporting efforts to reduce emissions by combining it with a halt to exploration for fossil fuels. Strengthening the terrestrial, freshwater and marine biosphere can complement climate-change mitigation and secure adaptation to climate change, biodiversity conservation, human well-being and natural life-support systems. This will also help preserve nature’s contributions to humankind and achieve a long-term stabilization of the climate.

Improved nature conservation also plays an essential role in preventing zoonotic pandemics: establishing protected-area systems, implementing an integrated land-scape approach and regulating hunting and the wildlife trade – taking into account the rights of Indigenous peoples and possible side effects on other sustainability goals – are important starting points for reducing contacts between humans and wildlife. Research into such preventive strategies should be stepped up.

For regions where the limits of adaptation to environmental and climate change will be reached in the foreseeable future and the well-being of humans, animals and plants is under threat (Figure 4), orderly and regular forms of human migration should be developed. The migration of species should also be facilitated by creating networked protected areas and ecosystems.

However, the global goals for biodiversity, the climate and sustainability for 2030 and beyond are likely to be missed if the causes of climate change and biodiversity loss are not sufficiently overcome and if measures to comply with current agreements and goals do not increase in pace and scale as specifically required.

Pollution: The global increase in human-made pollution is a major health risk for people and nature. This can be reduced by means of a circular economy and controls on emissions.

Compounds with adverse health effects are released during production and consumption processes that are not managed in closed cycles. The problem of pollution could be reduced in the future as a side effect of climate-change mitigation measures in some areas. However, it could also shift to new substances and applications, e. g. in the course of the energy or mobility transition. For this reason, there must be a greater political focus on the issue of global pollution with hazardous substances right now – i. e. at a time when combatting climate change is a top priority on political agendas. Dealing with this issue could also generate co-benefits for biodiversity and climate-change mitigation.

Figure 4

Global urgency governance

There is an urgent need for a form of global environmental and health governance that turns a healthy life on a healthy planet from a utopia into a realizable mission. Such a form of governance must be based on inclusive values that respect human dignity and a rules-based international order. The 2030 Agenda, the Paris Climate Agreement and the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework should serve as its orientation framework. There is also a need for globally coordinated, accelerating, long-term governance that responds to the urgent need for effective action. Global urgency governance, as recommended by the WBGU, is characterized by the following features:

- interdepartmental, cross-scale and coherent policy-making based on systematic coordination processes between outward- and inward-facing policy fields and oriented towards the guiding principle of healthy living on a healthy planet.

- forms of governance and process design that substantially accelerate transformation processes towards sustainability. Their features range from regulatory approaches, incentive structures and bureaucracy reduction to actor mobilization through involvement and inclusion.

- a long-term, future-shaping perspective that is simultaneously radically effective in the short term. It is important to maintain room for manoeuvre in the medium to long term. At the same time, the dynamics arising from the interplay of interdependent global crises should be dealt with powerfully, with intelligent reflection and by democratic dispute.

There are no blueprints for such urgency governance. It should be developed locally, regionally and nationally according to the respective sustainability challenges, adjusted to the circumstances and designed to be adaptive – while always guided by the vision of healthy living on a healthy planet.

> strengthening and implementing the 2030 Agenda as a global orientation framework and a mandate for action;

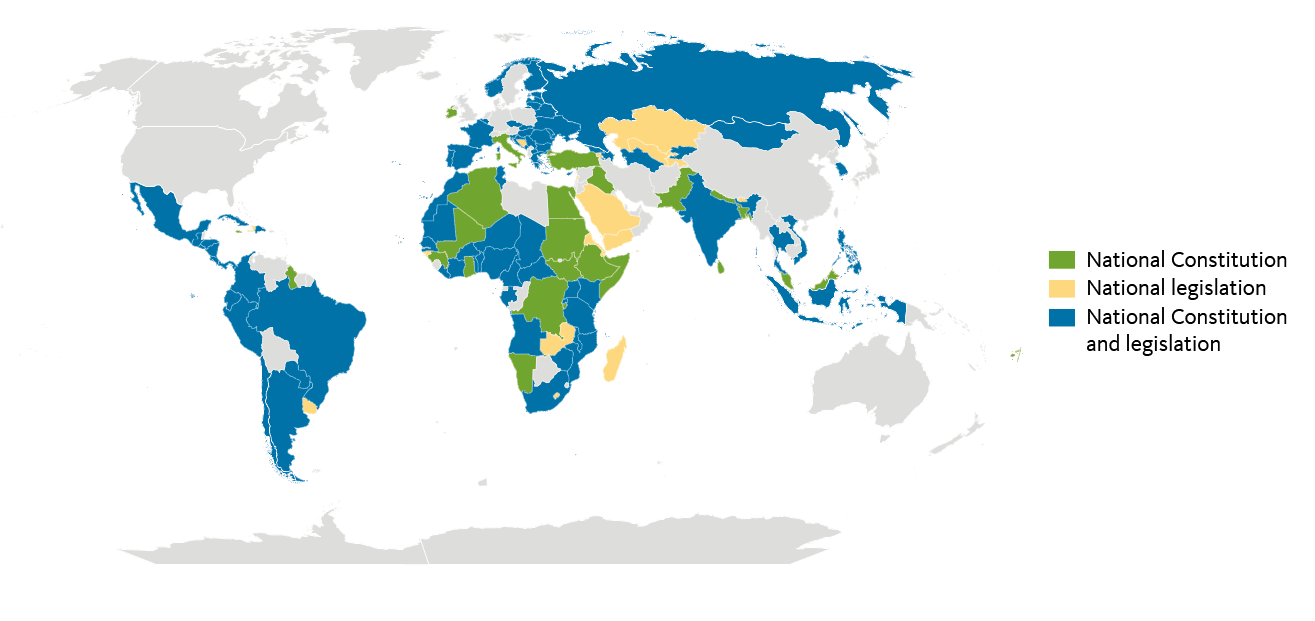

> integrating a human right to a healthy environment as a guiding principle and monitorable benchmark in national constitutions, especially in Germany’s Basic Law and the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, so that civil society can take the state to court to force it to take or stop certain actions (Figure 5);

> establishing a cooperative assumption of responsibility oriented towards the guiding principle of ‘Health in all Policies’:

> already making a start now to create arenas for discourse and actor structures to develop a post-2030 agenda for healthy living on a healthy planet.

Figure 5

Harnessing the transformative potential of health systems

Many health systems around the world are not meeting the new challenges posed by global environmental change – because of their curative focus, which in some cases includes the overprovision of medical services, a lack of preparation for the new health risks, and a large ecological footprint. Yet health systems are key to protecting and improving health; it is therefore imperative to develop them further, especially in the face of the new challenges. A key role is played here by environmentally sensitive health promotion and preventive healthcare, where healthy ecosystems are recognized as a resource and a prerequisite for health, and environmental changes are taken into account as major determinants of disease. In this way, health systems can make a decisive contribution to the promotion of healthy and sustainable lifestyles and to the creation of health-promoting living conditions. Transformations towards sustainability, adaptation to environmental change and strengthening resilience can create the right conditions for appropriate healthcare while respecting planetary guard rails. Resilience in health systems should address not only the risks of climate change, but all anthropogenic environmental changes, especially pollution and biodiversity loss. A key aspect here is the security of supply, which must still be ensured in the event of unexpected and unlikely future events. Since social inequalities have a significant impact on health, health systems and their governance should be developed in a way that treats solidarity and inclusion as core elements and gives vulnerable groups special consideration. The WBGU recommends significantly strengthening environmentally sensitive prevention and health promotion in health systems by enabling health professionals to promote healthy and sustainable lifestyles and to educate patients on environmental health risks and adaptation measures. This requires the provision of the corresponding training at all levels, the improvement of personnel resources and an adjustment of remuneration systems. Public health services should be significantly expanded, networked and their tasks extended to enable them to initiate and coordinate cross-sectoral cooperation for structural prevention (health-promoting design of working and living conditions).

Education and Science

Education and science occupy key positions in the vision of healthy living on a healthy planet. However, their transformative potential for the health of people and nature can only unfold globally if empirically based answers to research and education questions are developed worldwide in a context-specific manner, and networks for reflection and implementation are developed between politics, science, the private sector and civil society. This will require reducing the significant differences between national science systems, promoting transregional partnerships on the basis of reciprocity, and the systematic promotion of education for healthy living on a healthy planet worldwide.

By bolstering a comprehensive health perspective, Education for Sustainable Development can also come to mean education for healthy living on a healthy planet. It should firstly enable and promote knowledge, attitudes and skills relating to environmental and human health throughout life, and secondly encourage sustainable action within the educational institutions themselves, thereby developing a role-model function for daily action. Participation and transdisciplinarity are important here.

The vision of healthy living on a healthy planet needs science to help shape society’s future on a global scale – in an interaction between research, consulting and the promotion of young scientists at the interfaces between health science and the natural and social sciences. Research in partnerships between scientists from countries of different income groups and regime types is required, as well as continuous, iterative development processes of ideas and technologies, and the successive transformation of institutional guidelines and everyday cultural practices. To achieve this, it is necessary to strengthen underfunded science systems worldwide and to ensure the ability to speak and act on a common basis as a global society – by means of transregional cooperation between science, science policy and science funding.

More on the Subject

Voices to this Report

"Healthy Living on a Healthy Planet" is a critical and timely synthesis of priority transformations needed in governance, research, planning, and education at all scales, to promote the health and well-being of every individual, today and in the future, while simultaneously healing the damage from and preventing further climate change, biodiversity loss, and pollution. Focusing on health promotion and equity can facilitate rediscovering the intrinsic interconnectedness of all life on earth; and promote effective approaches to increase the resilience and sustainability of people and nature.

Kristie L. Ebi, Professor, Center for Health and the Global Environment (CHanGE)

University of Washington, USA

It is becoming increasingly urgent to promote an integrated view of the close link between the environment and global health. We can no longer afford to think and treat these policy areas, which are central to our future, separately. The WBGU flagship report comes at the right time and offers real added value - on the one hand through a clear analyses of the challenges and on the other hand through concrete proposals for rethinking global health governance. Now it is time to act.

Prof. Dr. Ilona Kickbusch, Director, Digital Transformation of Health LAB, University of Geneva; Founder, Global Health Centre, Graduate Institute, Geneva; Chair, World Health Summit

PDF Downloads

Deutsch

- Download: Zusammenfassung (PDF barrierefrei 3,4 MB)

- Download: Zusammenfassung (eBook, epub 1,2 MB)

- Download: Vollversion (PDF 25 MB)

English

- Download: Summary (PDF navigable 3 MB)

- Download: Summary (eBook, epub 2.1 MB)

- Download: Full Version (pdf, 21 MB)

Commissioned Expert's Studies

External expert studies are comissoned by WBGU, the responsibility for the content rests with the author.

- Download: Dr. Sabine Baunach: Anpassung von Gesundheitssystemen an bestehende und zu erwartende Umweltveränderungen in Low and Middle Income Countries (PDF 1,3 MB)

- Download: Beatrice Dippel: Traditionelle Heilpraktiken: die Indonesische Praxis des Jamu (PDF 1,1 MB)

- Download: Beatrice Dippel: Die partizipative Aushandlung von Zukunftsplänen: Singapurs Umgang mit den Auswirkungen des Klimawandels (PDF 1,1 MB)

- Download: Dr. Andreas Mandler: Wissenstransfer im Kontext von Beratungssystemen (PDF 1,3 MB)

- Download: Dr. Franziska Matthies-Wiesler unter Mitarbeit von Lilly Leppmeier: Inhalte der Forschungsprogramme zu Gesundheit und Umwelt – Recherche und Deskription (PDF 2,3 MB)

- Download: Dr. Franziska Matthies-Wiesler: Inhalte der Forschungsprogramme zu Gesundheit und Umwelt – Auswertung und Analyse (PDF 7,6 MB)

- Download: André Ullrich, Annika Baumann, Antonia Köster, Hanna Krasnova: Sustainable Digitalization: At the Intersection of Digital Well-Being, Health, and Environment (PDF 1,4 MB)