Carbon dioxide poses double risk to oceans and coasts

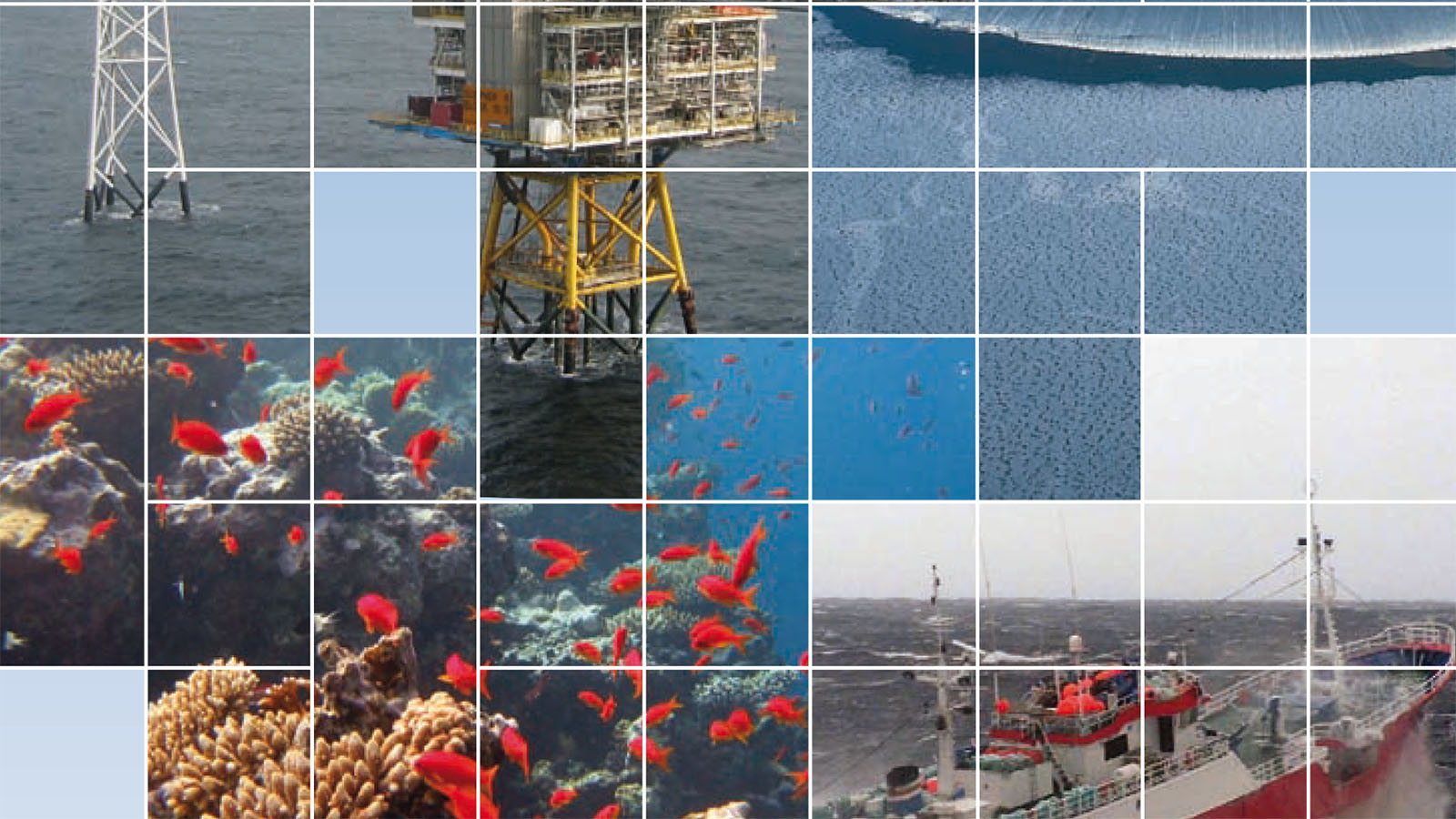

Latest research findings show that failure to check mankind’s emissions of carbon dioxide will have severe consequences for the world’s oceans. The marine environment is doubly affected: continuing warming and ongoing acidification both pose threats. In combination with over-fishing, these two threats are further jeopardizing already weakened fish stocks. Sea-level rise is exposing coastal regions to mounting flood and hurricane risks. To keep the adverse effects on human society and ecosystems within manageable limits, it will be essential to adopt new coastal protection approaches, designate marine protected areas and agree on ways to deal with refugees from endangered coastal areas. All such measures, however, can only succeed if global warming and ocean acidification are combated vigorously. Ambitious climate protection is therefore a key precondition to successful marine conservation and coastal protection.

In its report, WBGU shows that climate change is having severe impacts on the state of the oceans. Human activities are unleashing processes of change in the oceans that are without precedent in the past several million years. Three processes are critical: ocean warming, ocean acidification and sea-level rise. All three are a direct outcome of the atmospheric enrichment of pollution with greenhouse gases, especially carbon dioxide. To minimize the risk to the oceans and marine life it will thus be crucial to stem the increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide in time. WBGU stresses the need for a rapid response: because of the major time lags, human action now will determine the state of the oceans for many centuries to come.

Ocean acidification is advancing

The carbon dioxide released by human activities not only alters the atmospheric radiation balance and thus drives climate change. Carbon dioxide also dissolves directly in seawater. This causes rapid acidification of the oceans, which is already measurable today. If no action is taken, acidification could already reach a level within this century that will be greater than has probably occurred at any time for many millions of years. Furthermore, this process will be irreversible for a very long period of time. Acidification presents particular threats to calcifying marine organisms, such as corals, that have a key function in marine food webs and global biogeochemical cycles.

Oceans are warming, sea ice is melting

Warming seawater is threatening numerous marine ecosystems and fish stocks. This development poses incalculable risks, especially to human food security: about 15 per cent of the animal protein consumed worldwide derives from fish. One of the most visible consequences of warming is the retreat of Arctic sea ice. Over the past 30 years, summertime ice cover has declined by about 20 per cent. Without action to mitigate climate change, the Arctic Ocean is projected to be practically ice-free in summer by the end of the 21st century. This would have far-reaching consequences for climate worldwide.

The destructive force of cyclones is mounting

Observations and modelling results indicate that while climate warming does not increase the total number of tropical cyclones, it gives them greater destructive force. Tropical sea-surface temperatures have warmed by only half a degree Celsius, while an increase in the energy of hurricanes by 70% has been observed.

Sea-level rise is accelerating

Due to the melting of inland glaciers and continental ice sheets, in combination with the expansion of seawater that is a direct result of warming, sea levels are rising. The average global rate of rise throughout the 20th century was 1.5–2 centimetres per decade. Satellite measurements show that sea levels have risen by 3 centimetres in the past decade alone. Should the sea rise by more than 1 metre from the pre-industrial level, WBGU fears that the adaptive capacity of coastal societies will be overstretched.

WBGU recommends: Limit acidification and temperature rise

Adaptation measures can only succeed if sea-level rise, ocean warming and ocean acidification are limited to tolerable levels. The only way to do this is through aggressive climate protection policies. WBGU has already recommended previously that the rise in global mean temperature be limited to a maximum of 2 degrees Celsius above the pre-industrial level. Ocean conservation is a further reason for imposing this limit. Furthermore, in order to restrain acidification it is essential to reduce not only emissions of the overall basket of greenhouse gases, but also to ensure that carbon dioxide emissions in particular are sufficiently abated. It follows in WBGU’s view that global anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions will need to be approximately halved by 2050 from 1990 levels.

WBGU recommends: Strengthen the resilience of marine ecosystems

To strengthen the resilience of marine ecosystems to elevated seawater temperatures and acidification, it is essential to manage marine resources sustainably. In particular, over-fishing must be stopped. In addition, WBGU recommends designating at least 20–30 per cent of the global marine area as conservation zones. The international community has already adopted goals in this regard, for instance at the World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg. These must now be implemented, and the regulatory gap for the high seas closed by adopting an appropriate international agreement.

WBGU recommends: Develop new strategies for coastal protection

About every fifth person lives within 30 kilometres of the sea. Many of these people are put at immediate risk by sea-level rise and hurricanes. Coastal protection is thus becoming a key challenge for society, not least in financial terms. National and international strategies for mitigation and adaptation need to be further developed and harmonized. This includes plans for a managed retreat from endangered areas. In developing countries, financing needs to be secured by means of both existing and innovative financing instruments such as micro-insurance.

WBGU recommends: Give legal certainty to refugees from sea-level rise

At present, international law neither establishes a commitment to receive people who are forced to leave coastal areas or islands because of climate change, nor is the cost question resolved. Over the long term, a quota system is conceivable, under which states would have to adopt responsibility for refugees in line with their greenhouse gas emissions. This will require formal international agreements and the establishment of dedicated funds for international compensation payments.

WBGU recommends: Use carbon dioxide storage only as a transitional solution

To mitigate emissions, carbon dioxide can be captured in energygenerating facilities and then stored in geological formations on land or under the sea floor. Direct injection into the deep sea is a further option under debate, but this lacks permanence and harbours a risk of ecological damage in the deep sea. WBGU therefore recommends prohibiting the injection of carbon dioxide into seawater in general. In contrast, storing carbon dioxide in geological formations under the sea floor can present a transitional solution for climate protection, complementing more sustainable approaches such as enhancing energy efficiency and expanding renewable energies. Permits should only be granted, however, if such storage is environmentally sound and is secure for at least 10,000 years.